(AFP) Iraq on Monday remembers the 20th anniversary of the US-led invasion that toppled dictator Saddam Hussein, but no official events have been planned.

This country – a rich oil producer – remains traumatized by the years of conflict and sectarian violence that followed the operation that began on March 20, 2003.

Although the country has managed to establish a semblance of normalcy, it still faces immense challenges, such as political instability, poverty, and corruption.

Neighboring Iran, a Shiite-majority country and enemy of the United States, now has a lot of local influence, as the Shiite population has been freed from the yoke they suffered under Hussein’s Sunni regime.

The government has no events planned and on the streets of Baghdad people seemed more concerned about the arrival of the fasting month of Ramadan this week.

“It is a painful reminder for the country,” said Fadhel Hassan, a 23-year-old journalism student. “There was a lot of destruction and many victims,” he added.

The U.S. invasion was ordered by Republican President George W. Bush in a context marked by the September 11, 2001 attacks launched against the United States by the terrorist group Al-Qaeda.

Bush – backed by then British Prime Minister Tony Blair and Spanish Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar – argued that Hussein posed a greater threat and was developing weapons of mass destruction, although no such weaponry was ever found.

- Succession of conflicts –

The invasion, involving 150,000 American troops and 40,000 British fighters, succeeded in overthrowing Hussein’s government in three weeks. On April 9, the invading forces took control of Baghdad.

Around the world, television networks showed images of American soldiers toppling a statue of Hussein in Baghdad.

Shortly after, Bush declared “mission accomplished,” but the invasion led to rioting, looting in the streets, and chaos compounded by the U.S. decision to dissolve the Iraqi state, ruling party, and army.

When U.S. troops withdrew, the balance of the war was more than 100,000 Iraqi civilians dead, with 4,500 killed on the U.S. side, according to the Iraq Body Count organization.

The invasion marked the beginning of the bloodiest period in the history of Iraq, which first suffered a civil war between 2006 and 2008 and then suffered the occupation of part of its territory by the jihadist group Islamic State (IS).

Successive governments “have failed to fight corruption,” lamented Abas Mohamed, a 30-year-old engineer living in Baghdad. “We are going from bad to worse. No government has given anything to the people,” he said.

War in Iraq: A Lie and its Long Consequences

(DW) The killing continues two decades later: in February 2023 alone, at least 52 civilians died in Iraq in shootings, bombings, and other attacks. The violence is an echo of the war in Iraq launched by the United States on the night of March 19-20, 2003.

The Arab country could oppose little to the “shock and awe” campaign waged by the “coalition of the willing,” which included the United Kingdom, Australia, and Poland, under American leadership. Within three weeks, Saddam Hussein and his brutal dictatorship had disappeared from the map. Another three weeks later, and from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, a triumphant President George W. Bush announced “mission accomplished.”

By this time, according to Pentagon data, the US and its allies had dropped 29,166 bombs and missiles on the enemy country. Much of the local infrastructure lay in ruins. The British NGO Iraq Body Count estimates the number of civilian deaths at 7,000.

Thus concluded the major military operations, but at the same time began a long and fatal phase of occupation, which in total cost between 200,000 and 500,000 lives (depending on the estimate). In 2006, the medical journal The Lancet counted 650,000 “additional deaths.”

American troops withdrew in 2011 – only to return soon, in order to help fight the so-called “Islamic State,” a brutal fundamentalist group born out of the wreckage of Hussein’s Baathist regime. According to the German Ministry of Defense, 120 Bundeswehr soldiers are currently stationed in Iraq.

Winning the war, losing the peace

Military adventurism was “one of the last expressions of the West’s hubristic belief that it was capable of reconfiguring a country and a regional order to suit its preferences,” condemns Dan Smith, director of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (Sipri).

Turning Iraq into a Western-style democracy has proved more difficult than US decision-makers would initially like to believe. The Iraqi patchwork of ethnic and religious complexities overwhelmed an insufficiently prepared occupying administration.

A car bombing of the United Nations compound in Baghdad on August 19, 2003, which claimed 22 victims, set the stage for a ruthless and deadly insurgency.

“If the mission was to liberate Iraq from terror, to re-energize it and strengthen security at all levels, it was a total failure,” former UN Secretary-General Javier Solana summed up in 2018 in a commentary for the Project Syndicate platform.

Violations of international law, torture

This war was “a use of force contrary to international law and a violation of the UN Charter,” assesses Kai Ambos, a legal expert at Georg-August University in Göttingen, central Germany.

“The invasion of Iraq was not based on a UNO resolution. So that leaves only self-defense as a possible justification for the use of force.” Yet there was no case of self-defense, finishes Ambos. Kofi Annan, UN secretary-general at the time, shared this view, having called the war in Iraq illegal under international law.

Germany refused to take part, but supported the offensive, granting overflight rights and protection to the American military bases on its territory, as well as contributing secret information and funds. Thus, according to Ambos, Berlin “instigated and was complicit in an act contrary to international law.

At the time of the invasion, in an article for the FAZ newspaper, the prominent German philosopher Jürgen Habermas stated that one consequence of Washington’s decision to break international law by going ahead with the war had been “to give superpowers and a disastrous example” to follow.

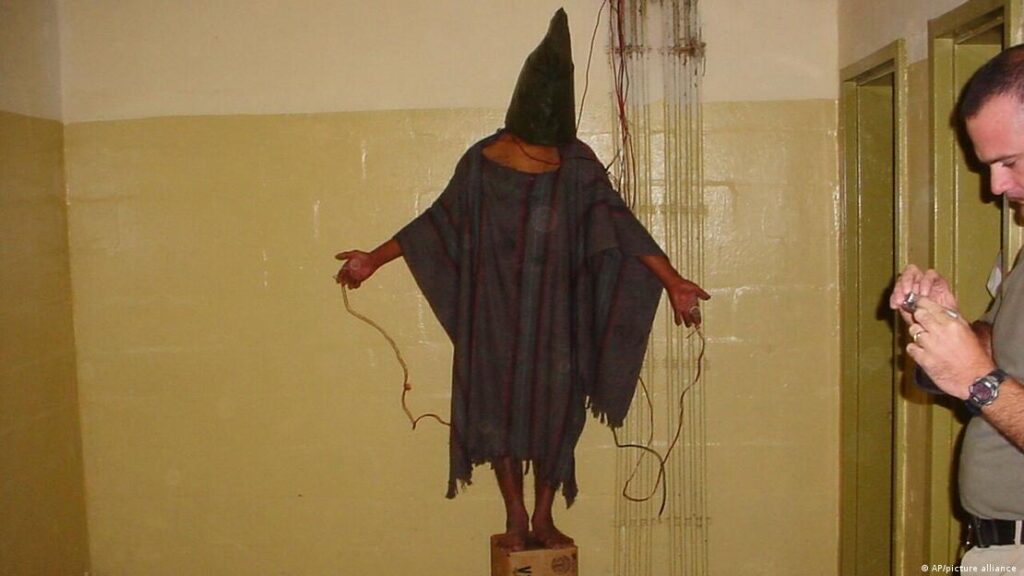

The United States’ global reputation fell even further with the revelation of war crimes and torture. By early 2004 at the latest, the whole world knew the name Abu Ghraib, the infamous prison of Saddam’s regime, which did not change much when the US military took it over: leaked photos revealed cruel physical and psychological torture against the inmates.

In addition, there have been incidents of American violence against civilians. In 2005, members of the Navy killed 24 unarmed citizens in Haditha in central-west Iraq. Two years later, in Baghdad, employees of the security firm Blackwater opened fire on a crowd, killing 17. In a video leaked by Wikileaks, a military helicopter fired on civilians, killing 12, including a journalist from the Reuters news agency.

Military aggression under false reasons

The two reasons claimed by the Americans to justify the war were lies: no weapons of mass destruction were found after the invasion; and Iraq did not participate in the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 on American soil, Saddam did not even have connections with Osama bin Laden and the Al Qaeda terrorists. The secret information on which such claims were based was either false, or exaggerated.

“The case is that they had decided what they wanted to do, and then they tried to find reasons for it,” explains Stephen Walt, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School. “It’s not that the intelligence was informing the decision: they manipulated it or ‘carved it up’ to justify what they had already decided to do.”

The apex of this public influence campaign was on February 5, 2003, when Secretary of State Colin Powell went to the United Nations to present “evidence” of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction programs, including attempts to acquire nuclear weapons.

After leaving the Bush administration, Powell was one of the few senior U.S. officials to regret his role in the country’s path to war, calling the speech at the UN “a stain” on his record.

Rules-based order or “do as I say, not as I do”

At least since the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, regime change in the Arab country had been on the American political agenda. The Bush presidency was already considering taking care of Saddam Hussein’s regime upon taking office, months before the 9/11 attacks.

“Saddam posed a challenge to the United States simply because he had survived after the Persian Gulf war. The U.S. counted on him being overthrown, but he held his own,” explains Stephen Wertheim, an associate member of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace foundation.

“He was an obstacle to the exercise of American hegemony in the Middle East,” he continues, and the September 2001 attacks were the chance that gave the Bush administration “wide availability to channel public anger and shape the reaction.”

This era coincided with the peak of post-Cold War American power, a fact that, for Harvard’s Professor Walt, is inconsistent with the “rules-based order” that the U.S. normally promulgates: “It’s a set of rules in the writing of which we’ve had enormous participation, and which, of course, we feel free to violate when it doesn’t suit us to follow them.”

For Kai Ambos, this inconsistency is one reason why, two decades later, countries such as Brazil, South Africa, and India are distancing themselves from the American call for support for Ukraine against the Russian invasion, and refusing to participate in sanctions on Moscow: “The ‘Global South’ is well aware of this apparent ‘double standard.’ And the bill for past actions is now coming due,” concludes the German jurist.