Maj Vinícios Martins do Vale

U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Jack Sullivan recently issued a warning to the international community about the possibility of Iran supplying Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS), better known as “drones,” to the Russian Federation. The intelligence reports point out that the Russians, despite having native production of drone systems, need to replenish their stockpiles due to the inability of their defense industry to provide them at the speed required for their “special operation” in Ukraine.

The warning highlighted the advanced stage that Iran’s drone development program has reached in recent times. Started during the war against Iraq in 1980, Iranian drone production has demonstrated a high degree of combat effectiveness during the recent conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. U.S. and Israeli officials already consider Iran’s drone program a threat to the stability of the region and are seeking to develop strategies to contain it.

Like Turkey, Iran has presented its drones as a propaganda asset. They would be proof of the self-sufficiency of its defense industry, the target of several international sanctions. Supplied to irregular forces that act in several conflicts in the Middle East, they are used for power projection, acting in favor of Iranian strategies in the region. Recently, by establishing its first drone production line in an allied country, Iran has also demonstrated that it seeks to strengthen its international relations through this modern combat equipment.

Since 2008, the Armed Forces of Venezuela have acquired drones and technologies for their production from the Iranian government. This closeness of these countries in such a sensitive and modern area highlights the importance of the subject for analysts in the Latin American defense community.

First Steps

After the Iranian Revolution, which took place in 1979, Iran broke off the close relations it had with the United States of America (USA) in all fields, including the military. The following year, the bloody war against Iraq erupted. The Iranian army had to operate without American logistical support, which develops much of its military hardware, including drones for Intelligence, Reconnaissance, Surveillance and Target Acquisition (IRVA).

The war against Iraq lasted until 1988. During all this time, the Iranian armed forces invested resources to maintain the few remaining American drones and to manufacture new ones with their own technology, since international embargoes against arms sales deprived Iran of the possibility to acquire foreign drones. Thus, the Quds Aviation Industry Company was founded in 1985, which created the first Iranian drone, the Mohajer-1.

Although it was not a decisive factor in the direction taken by the war, Iranian authorities saw the numerous possibilities offered by the new technology. The production of images, used as a source of intelligence to follow the movements of the Iraqi army, was the main function employed, allowing the timely deployment of defenses near enemy concentration points.

Once the war was over, efforts to develop drones remained. During the 1990s several variants of the Mohajer series were produced, with constant increases in flight range and image acquisition and transmission capabilities. Besides the improvement in control and navigation capabilities, still very rudimentary at the time, there was also the search for means to provide new drones with offensive capabilities. Tests were started with air-to-air and air-to-ground guided missiles installed in the drones.

In 2010, Iran reaped the rewards of nearly two decades of investment with the creation of a drone with offensive capabilities. That year saw the unveiling of the Karrar, the first long-range drone with IRVA and strike capabilities. The equipment was developed by the Iran Aviation Industry Organization (IAIO), a company that absorbed the former Quds Aviation.

Marking the rapid pace of new drone development, the Shahed-129 (IRVA and high-performance strike drone) was introduced in 2012, which, after several advances, became the backbone of the Iranian drone system today. Its production was mirrored by reverse engineering procedures performed on a captured Israeli Hermes-450 drone, a technique employed several times by Iranian engineers to achieve rapid technological progress with low investment. The Saeqeh drone series, for example, is based on the U.S. Lockheed Martin RQ-170 Sentinel drone. In December 2011, a copy of the Sentinel crashed on Iranian territory and was captured by that country’s military. Iranian officials reported that they even authorized Russian and Chinese engineers to inspect the captured drone.

The Yasir is a small IRVA drone, also the result of reverse engineering. Based on the captured US drone Boeing ScanEagle, Iran started mass producing it and supplying it to militias linked to its armed forces.

In April 2020, the Iranian army announced that it would start receiving Fotros attack and IRVA drones. First displayed in 2013, the Fotros, according to Iranian sources, is one of the largest drones in its arsenal. It has a flight range of over 30 hours, a flight ceiling of 25,000 feet, and an operational range of 2,000 km, which makes its employment in attacking Israel’s territory possible.

Forms of Iranian drone employment

After the war against Iraq, Iran, at least officially, has not been involved in any other conflicts. Thus, the combat performance of its drone system could be observed through its employment with allied militias fighting “proxy wars,” most notably the wars in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

The various Iranian drones shot down and captured in Syria and Iraq gave the dimension of their use in the fighting. Initially, the use of Ababil-3 light drones employed for IRVA missions was the most common. As the conflict unfolded, Shahed-129 attack drones began to be identified; however, it is inferred that their infrequent use was due to the need for a runway of considerable length for their takeoff. Videos obtained from the drones’ IRVA capability, others exploiting the effects of their strikes, and some of opposing forces capturing this equipment are also strong evidence of their routine use in the fighting in these countries.

In the war in Yemen, Iranian-backed Houthi militias have demonstrated great skill in employing drones, particularly in attacking essential infrastructure and selectively eliminating targets.

In January 2019, a Qasef-2k drone, a modified version of the Iranian Ababil drone series, exploded in front of the stage of a military parade in Yemen’s capital Aden, killing several military officials. Among the dead was a general who heads the Yemeni army’s intelligence division. The attack generated international repercussions, with videos being shown on several TV news programs around the world.

Upon returning from exile in December 2020, the Yemeni government was attacked as soon as its aircraft landed at Aden airport. Ballistic missiles hit the airport, causing the authorities to be hurriedly evacuated to the presidential palace. Upon arrival, the motorcade was attacked by explosive-laden drones. Several civilians and officials were killed during these attacks, which demonstrated the ability of the rebel forces to carry out complex offensive actions by combining drones and missiles.

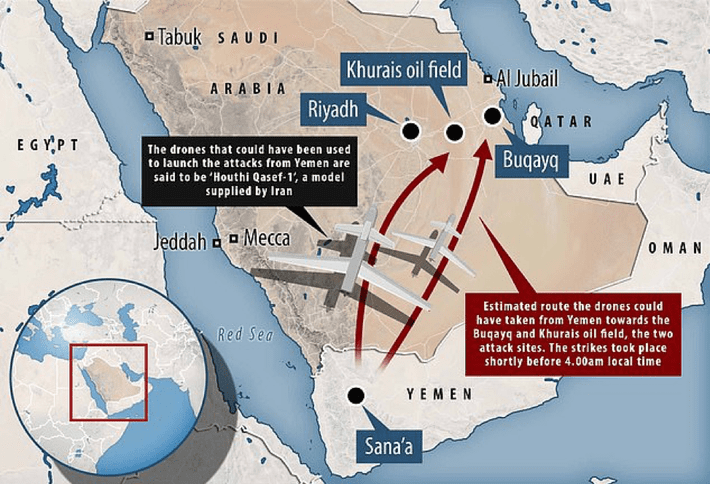

Attacks on Saudi refineries Abqaiq and Khurais

Houthi militias attacked in September 2019 two oil refineries in Saudi Arabia, the country that leads a military coalition supporting the Yemeni government. This action became emblematic for three aspects: the combined use of drone swarms with cruise missiles, the overcoming of anti-aircraft defense systems, and the long distance traveled by the weaponry to reach the target.

The attack generated repercussions on the international oil market, as the two refineries hit account for approximately 7% of the world’s oil processing. For its execution, the Houthis employed a large number of drones aiming to overcome the American Patriot anti-aircraft defense system.

To target the refineries, attack drones and cruise missiles were employed. International analysts who investigated the attacks were surprised by their level of precision and testified that the military capabilities of the Houthis, and therefore of the Iranian drones, reached a complexity and scale never seen before in the conflict.

This complex action sounded the alarm for vulnerabilities in the defense of critical infrastructure and demonstrated the possibility of using drones to disrupt global supply chains.

Regional Security Challenges

U.S. Central Command Commander Gen Kenneth McKenzie stated in April 2021 that Iranian drones scattered throughout the Middle East are a complex and serious security risk to the region. Because of them, the US has acted, for the first time since the Korean War, without complete air supremacy.

In June 2017, a Shahed-129 drone nearly hit US-led coalition troops in the Syrian War. It was the first time since the Vietnam War that a US troop suffered from an air strike.

With the construction of its first drone factory in a foreign country in Tajikistan, Iran shows that it is willing to transfer this technology for the sake of strengthening its international ties.

Venezuela’s National Bolivarian Armed Forces (FANB) unveiled the domestically manufactured “Antonio José de Sucre” (ANSU) drones, 100 for attack and 200 for surveillance, during a military parade in July 2022. The technology, developed in cooperation with Iranian technicians, shows that the influence of the Iranian drone program goes beyond the regional context of the Middle East, already affecting our own strategic environment.

Low-cost air capability

Drone development provides offensive and IRVA air capabilities to countries that cannot afford the heavy cost of a large conventional air force. In addition to state entities, the popularization of the use of Iranian drones by irregular forces in the Middle East highlights the threat that terrorist forces and criminal organizations will employ such equipment in their actions.

Iran, like Turkey, began to invest in the development of drones due to the restrictions on their acquisition by the major military powers. As a result of this work, it has achieved the capacity to produce effective drones at a lower cost compared to models from more advanced countries.

The Ukraine War, replete with examples of the use of modern drones in combat, will be another proving ground for these modern combat platforms, certainly affecting the directions that the development of these deadly weapons will take.

About the author:

Maj Vinícios Martins do Vale – The author is a Cavalry officer graduated from the Academia Militar das Agulhas Negras (AMAN) in the year 2007. He took the Psychological Operations Course (Op Psc) in 2014 and attended the Officer Training School (EsAO) in 2017. He obtained a master’s degree from EsAO through research on the Information Operations employed by the Russian Federation in the annexation of Crimea in 2014. He is currently serving in the 1st Psychological Operations Battalion, as part of the Psychological Operations Center.

*** Translated by the DEFCONPress FYI Team ***