After leaving the region behind, the United States is once again investing in Latin America. The move seeks to counter the expansion of Chinese influence in Latin American countries.

In recent months, US government officials have signaled the need for the country to pay more attention to Latin America, especially given the Chinese presence in the region. Meanwhile, China, which has been noted for a series of major infrastructure projects, has been diversifying its partnerships, such as in the electric vehicle chain, in what has been called the “new infrastructure”.

These initiatives reveal the international prominence that the region has gained in recent years, partly due to geopolitical conflicts such as the war in Ukraine and the trade dispute between Washington and Beijing. Latin America’s energy potential has also contributed to the region moving up the list of priorities for the West.

“Latin America has a large market, as well as being a rich source of energy and minerals. While the United States has moved away in the last decade, China has increased its presence in the region, strengthening commercial ties and investing in infrastructure,” say Christopher Garman, executive director for the Americas at Eurasia, and Julia Thomson, a researcher at the same consultancy.

“Some countries, such as Mexico, benefit more than others because of their proximity to the United States,” the experts point out, highlighting the phenomenon known as nearshoring – a strategy that takes production closer to consumer markets – with Washington seeking to secure its supply chain in countries that are closer and with which it has a greater alliance.

With the aim of expanding nearshoring across the continent, the US Trade Investment Act, which includes an investment of 14 billion dollars in Latin America and a tax reduction plan, is currently before Congress. In addition, the US Secretary of Commerce, Gina Raimondo, has sometimes mentioned the possibility of Brazil being part of the country’s investment chain in semiconductors, one of the most sensitive issues in trade disputes today.

For his part, diplomat Marcos Caramuru, who was Brazil’s ambassador to China, is more skeptical about Washington’s real ability to cope with Beijing’s investments in the region. “China works with state-owned companies, which often have a vision more closely linked to that of the government, which is not the case in the United States,” he points out, suggesting that for American private capital to reach the region, political will is not enough.

“New infrastructure”

Meanwhile, China is expanding its investment plans, especially focusing on what is being called “new infrastructure”. For Margaret Myers, director of the Asia and Latin America program at the Inter American Dialogue, and author of a recent study on the subject, these sectors include the manufacture of electric vehicles and other cutting-edge industries, telecommunications, renewable energy and ultra-high voltage transmission lines.

In recent months, Chinese automakers BYD and GWM have made a series of announcements for new projects in the region, especially in Brazil. One of the most recent was for the former to produce batteries in the Manaus Free Trade Zone.

China’s interest in so-called “new infrastructure” is largely driven by its own efforts to improve its economy, Myers points out. According to her, Beijing notes that future growth, even at moderate rates, will require a greater degree of competitiveness and even domination of frontier sectors.

According to Myers, the projects are generally smaller in scale than the large, flagship New Silk Road projects in Latin America, and tend to incur fewer operational, financial and reputational risks. “This is important at a time when China is seeking to reduce the risk of the initiative,” he says.

The boom in large-scale construction financed by Beijing has left a legacy of important works, such as the port of Chancay in Peru, which is targeted by several countries in the region, but has not escaped controversy. In Colombia, the Hidroituango dam, the largest in the country, was marred by contractual problems with Chinese companies. China’s initiative has also driven up national debts, something that has been particularly marked on the African continent, adds Caramuru.

In Brazil, amid the enthusiasm for Beijing’s investment promises, the Paraíba Public Prosecutor’s Office (MPPB) opened an extrajudicial procedure to investigate a project proposing the construction of a deep-water port and a futuristic city in Mataraca, on the northern coast of Paraíba. The planned investments would amount to R$9 trillion, which raised suspicions.

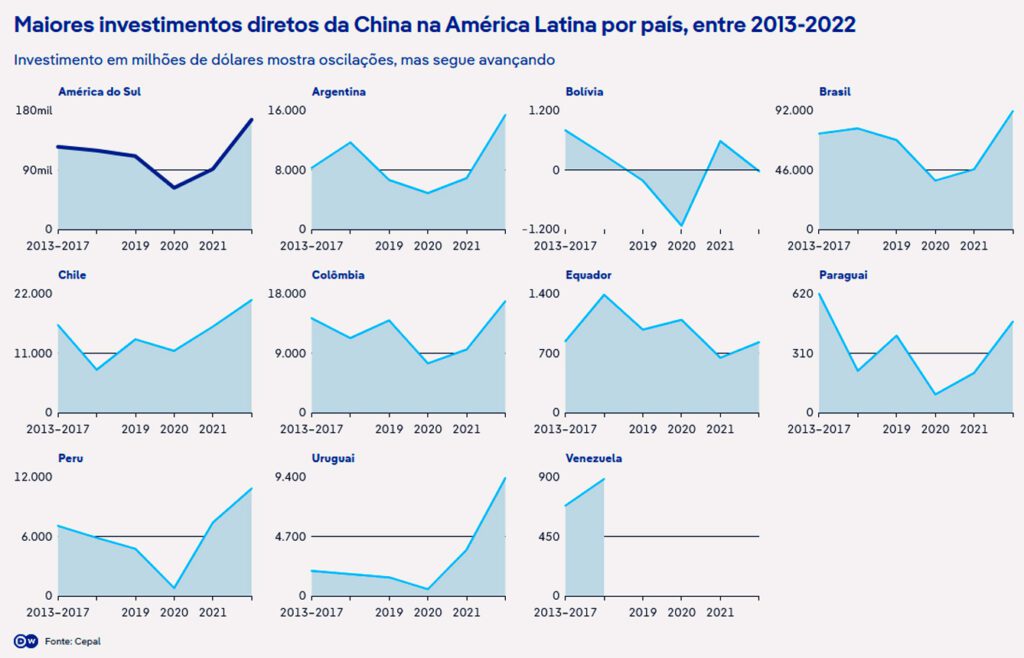

A study by the Inter American Dialogue revealed that data on Chinese foreign direct investment in the region showed a notable downward trend in project announcements in recent years. The drop is attributable to numerous factors, but is at least partly related to an ongoing recalibration of investment priorities by China’s government and its companies, it concluded. “China is betting on smaller, technology-intensive projects to grow its own economy and reduce the risk of its international presence,” Myers points out.

Non-alignment trends

Analysts agree that the countries in the region should maintain a stance without automatic alignments. “The picture in Latin America tends to be more pragmatic. If they bring jobs and investment, they will be welcome,” says Caramuru. The diplomat recognizes that Washington may even try to exert greater pressure to distance itself from Beijing, but he doesn’t believe that this will generate great results.

Eurasia’s analysts share this view and believe that this movement could occur at some point in the future, but they don’t see it as something close. “The tradition of non-alignment is a hallmark of Brazilian foreign policy, and that of most of Latin America,” they say. “American diplomats recognize the great commercial ties with China, but they are not going to force a choice. This was evident with the failure of the attempt to force Huawei’s exclusion in the adoption of 5G,” they recall, citing the episode in 2020 when there was pressure for Brazil not to adopt the Chinese company’s technology.

“It is clear that initiatives such as the announcement of the construction of a Huawei factory in Brazil, for example, could generate some consternation for the Americans, potentially causing a drop in the diplomatic temperature,” they point out. However, such an event in itself is unlikely to become a watershed in bilateral relations, the experts ponder.

“Nations like Peru and Chile exemplify this dynamic by maintaining trade agreements with both China and the United States, demonstrating the region’s ability to balance and sustain political and economic connections with both powers,” they conclude.

*** Translated by DEFCONPress FYI Team ***