By launching the “new Silk Routes” in 2013, President Xi Jinping took China on an unprecedented adventure in history. In a decade, Beijing has spent hundreds of billions of dollars, from Asia to the Americas, via Africa and Europe, on investments in infrastructure – but that’s not all. Today, more than 150 countries have joined what has become a label and, above all, a complex network of land and sea corridors around the world. Ten years on, what is the balance of the “project of the century”, in Xi Jinping’s words?

RFI

September 7, 2013. State visit to Astana, capital of Kazakhstan, and speech in the amphitheater of Nazarbayev University. The day will silently go down in history: “Let’s build an economic belt along the Silk Roads together.” With these words Xi launched his pharaonic project.

At the time, no one could have predicted how far-reaching and global the “One Belt, One Road” (or Obor) project would reach in the space of just a decade. A month later, the Chinese president was in Jakarta. “Let’s build a 21st century Maritime Silk Road together,” he warned, this time before the Indonesian parliament.

The term “Silk Road”, invented in 1876 by the German Ferdinand von Richthofen, does not match Xi’s undertaking. It harks back to a time when the powers of the Old Continent dreamed of a Eurasian railroad. The geographer gave his name to this long-distance network that for a long time crossed the Chinese desert to transport goods to Europe, as two empires organized world trade and profited from it.

The network would have functioned from the 2nd century BC until the 15th century AD, the beginning of the great colonizing conquests of the Europeans.

Purely a product of the Western imagination, the expression “Silk Routes” is full of ethnocentrism: it didn’t even include the “sea route” that has always linked China to the Indian Ocean. Moreover, these “routes” were organized neither by Europeans nor by the Chinese, but by merchants from Central Asia, with their caravans travelling from one oasis to another.

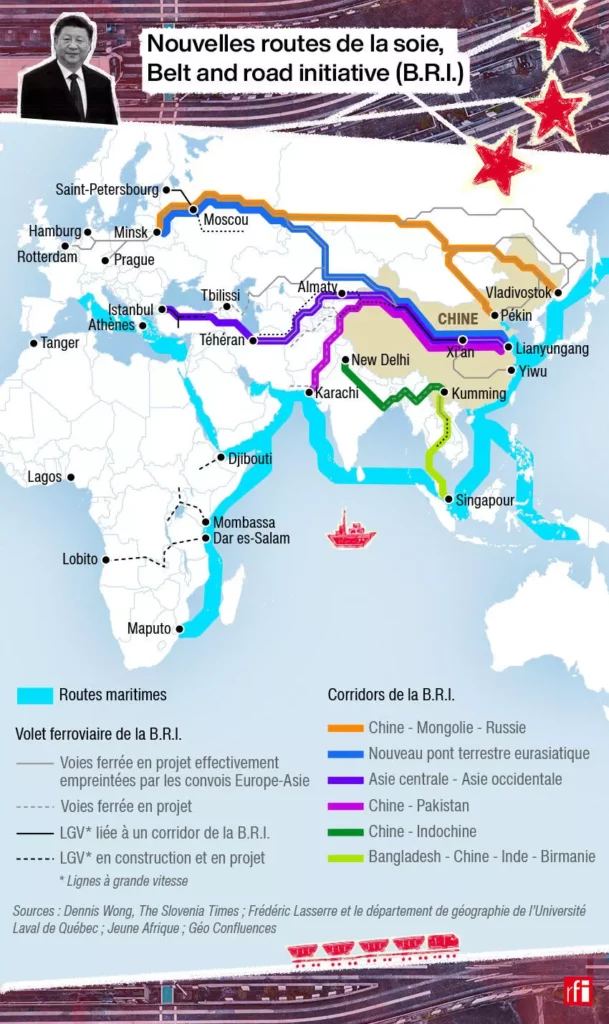

The ambition of the “new silk routes” is radically different, and unprecedented. This time, China wants prominence. It no longer wants to depend on trade routes under American influence, such as the vital Strait of Malacca, through which much of the world’s maritime trade passes. It wants a network of which it is the center, the financier and the main beneficiary – whatever the cost.

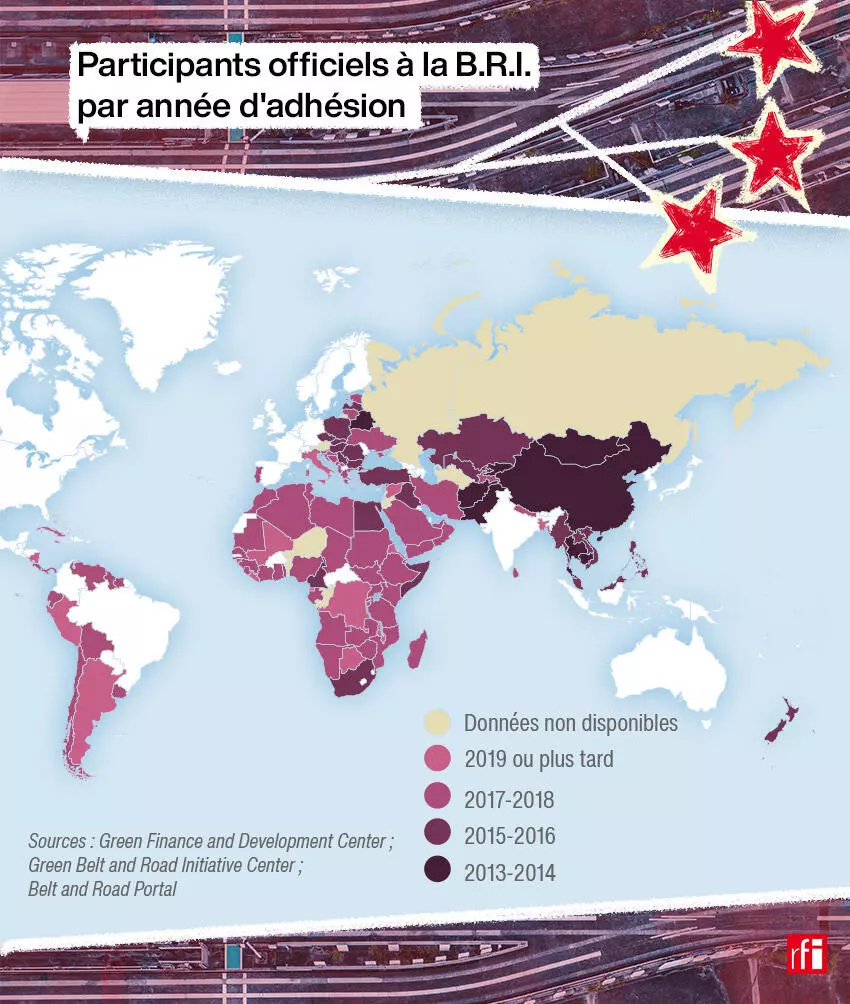

In a decade, it has released almost €1 trillion to finance transportation, energy and telecommunications infrastructure projects, among others. It creates a complex network of land corridors and maritime routes, and has managed to get more than 150 states to sign agreements to participate in the “New Silk Roads”.

They are now a label that is not just about “roads” or “belts”, going all the way to South America. They bring together an overwhelming majority of nations from the Global South, the developing countries often frustrated by the world economic order dominated by Westerners and Americans. Since the Marshall Plan, the world has never seen such ambition – and this worries the West, which sees China consolidating a gigantic instrument of global economic and political power.

The mechanism has been dubbed “debt trap diplomacy”: opening up access to strategic facilities in Asia, Africa, the Persian Gulf and even the Americas is increasingly proving to be Beijing’s real objective.

Financing African development

“In Africa, the results are quite controversial,” observes Xavier Aurégan, geographer and professor at the Catholic University of Lille. On the one hand, China has managed to integrate the vast majority of African countries, with the exception of Mauritius and Essuatini – which recognizes Taiwan.

“China has increased its financing capacities, much more than its investment capacities, by also rubber-stamping all infrastructure projects as part of the New Silk Routes, even those launched before 2013. From this point of view, the project is relatively successful,” Aurégan points out.

But on the other hand, “the Chinese global offer” is increasingly controversial. “Financing in exchange for contracts won by Chinese companies is questionable,” since it operates to the detriment of other international or African groups. The famous “win-win partnership” touted by China is reaching its limits.

“This financing of development in Africa generates consequences that China denounces when it is Westerners who benefit from the contracts,” the geographer points out, citing indebtedness, the creation of networks of influence, forms of dependency and all the local environmental and social impacts.

The outcome of this change in direction is still uncertain. Since 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has put a large number of projects on hold. Now, countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo are trying to renegotiate some of the contracts and agreements with China.

“It’s difficult to make a single assessment because the New Silk Routes have several branches,” observes Nadège Rolland. “They don’t just focus on infrastructure, whose investment has been declining since 2016, but also on other branches linked to the development of cooperation in health, education or changing international standards, which is the axis of the main effort. On this point, the results are much more positive from the point of view of the Chinese authorities, who have managed to promote many advances, especially in the developing world.”

The “multidimensional” nature of the BRI gives China some flexibility. During the pandemic, it is the health sector, or rather the “Health Silk Routes”, that are highlighted by Beijing and convey “vaccine diplomacy”.

Images of masks and other protective equipment distributed in boxes with a clearly visible Chinese flag circulate in all the media. What not everyone knows is that the expression “Health Silk Routes” has been used since 2017 in the speeches of the director of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, supported by China.

Alternative world order

With the “New Silk Routes”, China’s ultimate goal is not the financing of infrastructure in developing countries: it is the creation of a “community with a shared future”, in the words of Xi Jinping. This vague slogan hides what Nadège Rolland calls a “shift in international standards”.

This change has been taking place for several years, through China’s strategy in multilateral organizations, taking advantage of the withdrawal of the United States during the Donald Trump era to take up management positions in certain UN agencies. This tactic, however, doesn’t always work: Beijing is unable to change the balance of power with the West within the UN and its agencies. The result: China creates parallel organizations, in which it is in charge, to try to overthrow the world order.

“At a time when China was in trouble with the WHO, it positioned itself in Africa to create a disease prevention and control center in Ethiopia,” stresses sinologist Alain Wang, a professor at the Central Supélec School in the Paris region.

The Center for Disease Control in Africa, which was to be co-financed by China and the United States, was cut off from US participation under the Trump administration – and Beijing stepped into the breach. “China invested around €65 million to create a huge building in Addis Ababa,” continues Alain Wang.

The center, currently aimed at Africa, also has regional branches in Egypt, Gabon, Kenya, Zambia and Nigeria. “And it’s certainly going to multiply in Africa, but also outside Africa, perhaps in Latin America and Asia,” says the expert.

For the sinologist, this is where the BRI has a positive outcome for Beijing. “China has managed to unite around itself a number of large and small countries that will play a very important role in the future, positioning itself as the leader of a world that is the opposite of the Western world: a world where democracy doesn’t exist. A world of authoritarian countries.”

Moment of adjustment

What is the future of the “New Silk Roads”? For Xavier Aurégan, the project is “at a standstill” in a context where the country’s economy is slowing down. The drops in Chinese loans are clear: in sub-Saharan Africa, they fell by 65% in 2022 compared to 2021, according to the Green Finance & Development Center, a think tank linked to Fudan University in Shanghai.

“There are conflicting thoughts within the Chinese political elite,” continues the geographer. “One party believes that the BRI is perhaps finished, perhaps a little out of fashion, and that we should move on to something else. This something else is called Xi Jinping’s ‘new era’. Perhaps a new aspect of foreign policy will gradually be implemented,” analyzes Aurégan.

But this is not Nadège Rolland’s opinion. According to the researcher, several years have passed since the death of the BRI was announced, in vain. “Perhaps it appears less in Chinese diplomacy,” acknowledges the scholar, who mentions the competition of new labels: the “Global Development Initiative” or the “Global Security Initiative”.”After China reopened after the pandemic, the Chinese authorities visited several friendly countries and the BRI appears in the cooperation agreements signed in 2022 and even in 2023,” she points out.

The most recent example was the China-Central Asia summit in Xi’an on May 18 and 19. Xi Jinping invited five Central Asian leaders, to whom he offered a spectacle worthy of the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008.

The main theme of the meetings was “the Belt and Road initiative”, which continues to be one of the main instruments of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy. Proof: the Xi’an summit took place at the same time as the G7 meeting in Hiroshima.

The Western powers demonstrated a common front against the ambitions of China, which maintains its “unlimited” support for Russia, despite the bloodbath in Ukraine. The Russian invasion and Western sanctions have suspended part of the traffic of goods on the “silk railway routes” through Eurasia. But far from being discouraged, China has redirected its trains more directly to Moscow, promoting its “Trans-Caspian route”, which passes through Istanbul.

Now is the time for adjustments and rebalancing – and certainly not the burial of the “New Silk Routes”.