Colonel Marcos Luiz da Silva Del Duca

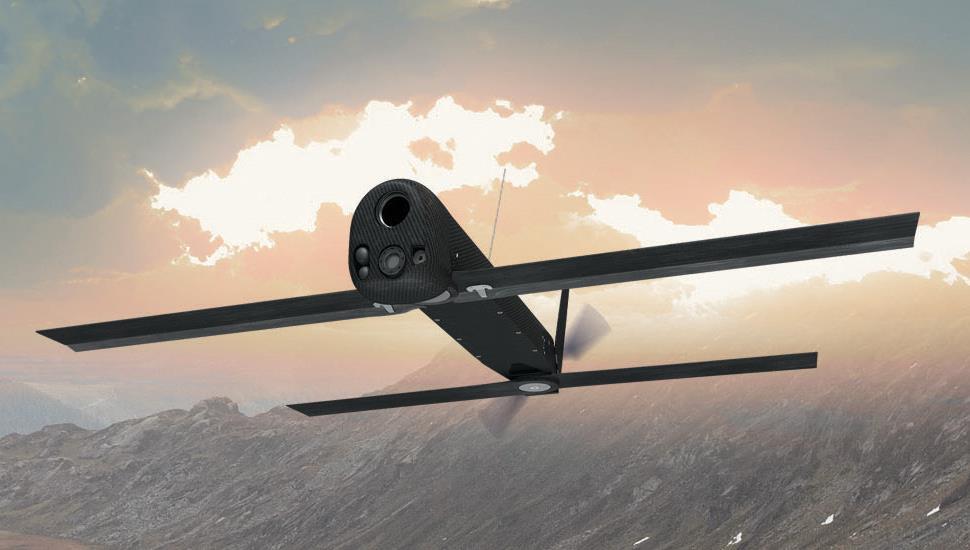

In the face of current armed conflicts, names such as Spectre, Punisher, Bayraktar, Reaper, Phoenix Ghost, Switchblade, and Vector have become increasingly common in the context of military operations. But what do these names represent? They are all names for military drones, a means of warfare in the fourth industrial revolution that uses sophisticated technology connected to artificial intelligence to defend the interests of various countries.

Investment in the development of unmanned combat aerial systems is a reality in the defense field of several states. Some of these systems fit into the sixth generation of combat aircraft, assuming that this generation will have autonomy, because certain models have sensors that enable a system based on artificial intelligence to detect, classify and decide to execute an attack autonomously.

These weapons gradually reduce the human presence on the battlefield, replacing combatant soldiers with weapon systems, often with autonomy in the critical functions of selecting and attacking targets.

In this sense, it is worth noting that this autonomy of systems, in the context of military operations, must be exercised within a legal framework conformed by International Law (basically, the International Law of Armed Conflict and/or the International Law of Human Rights), since it is human beings, and not machines and computer programs or autonomous drones, who apply and must respect the rules of the ILAC (the terms “International Law of Armed Conflict,” “International Humanitarian Law,” and “Law of War” can be considered synonymous).

The ILAC requires those who plan, also decide, carry out attacks, and analyze the application of its norms before executing an offensive, since the use of force during armed conflicts is not unlimited and imposes obligations, and must always take place within a specific legal framework.

In the conduct of military operations, constant care must be taken to spare the civilian population, civilian persons, and property of a civilian character. All possible precautions must be taken before an attack is carried out to prevent and ultimately minimize the incidental loss of civilian life, civilian casualties, and damage to property of a civilian character.

Given such a scenario, from the perspective of ILAC, some questions arise about the employment of autonomous unmanned combat air systems:

A. Do autonomous weapons have the ability to assess the collateral damage of an attack?

B. Can autonomous systems identify a legitimate military objective?

C. Can these systems employ a method or means of combat whose effects can be limited as required by ILAC?

D. Can autonomous weapons differentiate between a combatant and a civilian? Are they able to distinguish a combatant from a person out of combat?

E. Would autonomous systems have a better ability to identify military targets than combatants (human element)?

F. Could such systems apply the basic principles of ILAC (of military necessity, humanity, distinction, and proportionality) before an attack is executed?

G. Who would be held responsible if an autonomous weapon were to violate a ILAC standard?

H. Are these autonomous systems susceptible to attack and manipulation by hackers that could result in accidents and terrorist actions?

Based on the premise that wars without limits are wars without end, the limits imposed by the ILCA are fundamental to avoid the spiral of violence.

For example, Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, adopted in 1977, complements the protection afforded by the four Geneva Conventions and is applicable in international armed conflicts. It imposes additional limits on the way in which military operations can be conducted and further strengthens the protection of civilians.

According to Article 36, each Party is obliged to determine, during the study, preparation, acquisition or adoption of a new weapon, new means or new method of warfare, whether its employment would be prohibited in some or all circumstances by the provisions of this Protocol or any other applicable rule of international law. In this way, the ILAC seeks to regulate the development of weapons technology and the acquisition of new weapons by states.

But regardless of the aforementioned rule, evidence shows that in the recent armed conflicts in Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Ukraine, the use of autonomous air systems in the theater of operations is real, and that several countries and non-government groups already possess such tools of war. Their use is no longer an exclusivity of the United States of America (the country has led advances and investments in the area of autonomous air systems, especially after the events of September 11, 2001) due to the diversification of manufacturing companies (notably Israeli, Chinese, and Turkish companies) that have contributed to the widespread acquisition of these autonomous weapons.

Unfortunately, disconnected from the ILAC, there is evidence that attacks with autonomous military drones have caused a significant number of civilian deaths and damaged protected property, which, in theory, can be considered war crimes.

Articles 57 and 58 of the Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions present a series of precautionary measures to be taken before an attack is carried out and against its effects, respectively. In order that protected persons and goods are effectively spared, the behavior of combatants in military operations during armed conflicts is subject to restrictions. Thus, there are doubts as to whether the autonomous drones employed by various countries are capable of analyzing and making decisions before attacking a military objective.

In armed conflict, the right of parties to choose the means (weapons and weapons systems by which violence is done to the enemy) or the methods of combat (tactics and strategies applied in military operations to weaken or conquer an adversary) is not unrestricted. The ILAC prohibits the use of means and methods of warfare that are indiscriminate or cause superfluous damage and unnecessary suffering. The specific restrictions and prohibitions concerning the means of war (weapons) and the prohibition of methods of war were derived from the basic principles of the ILAC: distinction, limitation, proportionality, military necessity, and humanity. In this sense, would today’s autonomous military employment systems have the ability to respect such basic principles prior to the execution of an attack?

On the other hand, with regard to the use of force, every state (defined as a sovereign entity composed of a population, a territory and a governmental structure) involved in some armed conflict is, of course, an important bearer of rights and obligations under international law. It is therefore responsible for the acts of its officials when they are exercising official functions or in their capacity as de facto agents. However, when the decision to execute an attack on a military objective violates some ILAC standard, and it is carried out by an autonomous system, i.e. by a program based on artificial intelligence, who will be held responsible?

Due to the big questions about the use of autonomous military employment systems, it is important that states evaluate the human cost correctly before investing in the development or acquisition of such weapons.

Many countries have no interest in regulating the use of unmanned automated combat air systems, since this could limit their freedom of action during military operations. Thus, many states, especially those that have this combat tool, avoid discussions on the subject and prefer to remain in a gray area, that is, in a nebulous region of the ILAC.

This lethargy of countries before the discussions involving the dissemination of autonomous armed drones, a new weapon in the light of ILAC, is certainly contrary to the humanitarian principles advocated by Jean Henry Dunant, known as the father of the Red Cross, due to the legal, ethical, and moral issues surrounding the employment of such means of combat in the current scenario.

Finally, the use of autonomous armed drones in military operations is a Defense area theme that should be discussed by all of society. Its use is of interest not only to the combatants involved in the conflicts, but also to the civilian population, civilian people, and civilian assets, regardless of the theater of operations in which the armed conflicts are taking place.

-x-

About the author:

Colonel Marcos Luiz da Silva Del Duca – Colonel Marcos Luiz da Silva Del Duca is an infantry officer in the Brazilian Army. After completing the course of the Army Command and Staff School (ECEME), in Rio de Janeiro, he held the positions of Operations Officer of the 12th Light Infantry Brigade (Aeromobile) and ECEME Instructor. In 2019, he took the Course on International Law of Armed Conflict (CDICA) at the Superior School of War (ESG), Brasilia Campus. He is currently the Commander of the 2nd Border Company – The Sentinel of the Pantanal, a military unit located in the south-mato-grossense borderland strip with Paraguay, in the municipality of Porto Murtinho (MS).

*** Translated by the DEFCONPress FYI Team ***