Baltic country tries to contain the spread of disinformation from Moscow, but given its large Russian-speaking community, the task is difficult. For ethnic Russians living in Latvia, their language and culture are at stake.

Once part of the Soviet Union, Latvia gained its long-awaited independence in the 1990s and then became a member of the European Union (EU) and NATO. However, three decades later, the Soviet past still has a strong impact on the country.

Moscow’s imprint is especially present in Rezekne, a town of about 27,000 inhabitants located approximately 60 kilometers from the Russian border. On the surface, there is no visible difference between this Latvian city and small rural Russian towns.

Many residents live in Soviet-era apartment blocks with roofs covered by satellite antennas that receive the signal from Russian state TV. When walking through the city streets, you hear more Russian than Leto. There is a reason for this: almost half of Rezekne’s population is ethnic Russian, and many of the residents have little or no knowledge of the Latvian language.

Cities like Rezekne, with its large Russian-speaking populations, raise an important question: what influence does the Kremlin-controlled media have on the Latvian population, just over a quarter of which is made up of ethnic Russians?

Latvia bans Russian state media

Even before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, Latvian authorities were already beginning to remove Russian state media from the country. In August, the National Council for Electronic Media banned 20 Russian media outlets, deeming them a threat to Latvia’s national security.

But despite the ban, residents told DW that Russian state TV channels are still accessible via the internet and satellite dishes.

Maria Dubitska, a native of Rezekne, believes that the effect of Russian propaganda is especially apparent in her town.

“We are losing our friends and our neighbors. It hurts. Russian propaganda is like poison, it is dividing our society,” she told DW. “Ideas are circulating about the return of the Soviet Union, and all these ideas are transmitted directly into the heads of the people here,” he points out.

However, other Russian speakers think it’s a good thing that they can still access Russian state TV, arguing that the Latvian state should not limit media options.

“To form an opinion, you have to know both sides,” said Igor, who preferred not to give his last name. “Especially when there are many Russian speakers living in Latvia, why violate their rights?” he added.

Latvia’s Widespread Support for Ukraine

It is an interesting debate in a country that is among the top supporters of Ukraine, both in terms of military and humanitarian assistance. Recent polls indicate that 82% of Latvians support Ukraine against Russia. In this context, admitting to watching Russian state TV may be an unpopular stance.

“Nowadays, it is better to leave this question unanswered,” said Sergei, who also preferred not to reveal his last name.

Attitudes don’t change overnight

According to Arnis Kaktins, head of the Riga-based SKDS public opinion research center, Kremlin narratives still play a crucial role among many members of the Russian minority in Latvia.

“For decades, Russian speakers watched Russian propaganda, which was of high quality, and it worked,” he explains. “This shaped the worldview of many – and their attitudes cannot change overnight.”

Social media has also become an information battleground in recent years, explains Inga Springe, cofounder of Re:Baltica, a Riga-based non-profit investigative journalism organization.

“We see more and more disinformation in TikTok; it’s like the Old West. Some bloggers are saying how bad life is in Latvia and good in Russia,” he told DW. “They take existing problems and amplify them, like high electricity bills, and accuse the Latvian authorities. [The bloggers] don’t see the root of the issue, which is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that has raised prices.”

The media issue also touches on another broader concern for ethnic Russians in Latvia, many of whom are worried that their language and identity are at risk. A fear that, as Latvian officials say, the Kremlin knows how to exploit very well.

“There is no reason why Latvia should continue to maintain two parallel and totally separate information spaces,” Rihards Kols, a member of the Latvian parliament, told Foreign Policy magazine in March. “Russia uses the Russian language as a weapon through its media to divide, cause confusion, obfuscate and manipulate.”

Nika Aleksejeva, a researcher at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab, warned against generalizations about the Russian community in Latvia, justifying that it is not a homogeneous group.

“There are people who stubbornly do not learn Latvian and have more pro-Kremlin views,” she told DW. However, according to her, there is also a whole generation that grew up in the post-Soviet era. “They are thinking more like Europeans, although they use Russian in their homes.”

In its effort to promote the Latvian language, Riga passed a law that completely eliminates Russian from the school curriculum. The measure was considered by many in the Russian community as discriminatory. UN human rights experts have also expressed their concerns, saying that Latvian authorities have an obligation to “protect and defend the linguistic rights of the country’s minority communities without discrimination.”

Controversy over Soviet monuments

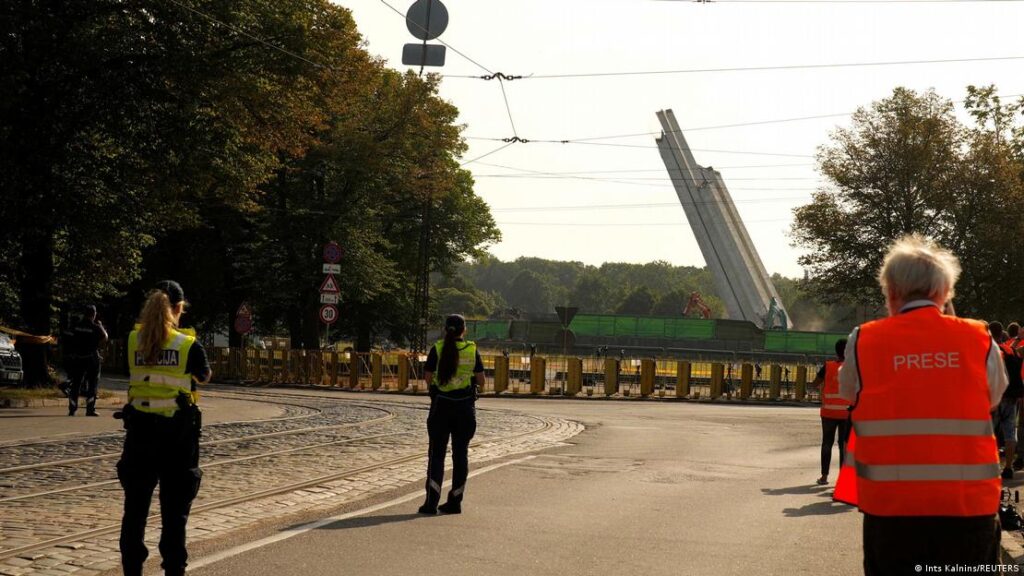

Another attempt by Latvians to distance themselves from Moscow has been the removal of Soviet memorials, of which there are about 300 in the country, according to expert assessments. For critics, these monuments glorify the Soviet era.

In July of last year, the Latvian Parliament began removing dozens of monuments, which had been erected to mark the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany in 1945.

For many ethnic Russians, the monuments are an integral part of history. However, in the opinion of many other Latvians, this is not quite the case.

“The monuments are not simply to remember those who fell in their struggle against fascism. With them, Russia brings its own version of history. Latvians do not see the Soviet Army as liberators, but as an occupying force,” said Kaktins of the SKDS research center, adding that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led Latvians to reconsider, figuratively and literally, the place of Soviet monuments in their country.

“It is clear now that memorials, glorifying the heroic and grandiose past, are one of the pillars of the current Russian ideology that enabled the war in Ukraine,” he added.

But Springe, of Re:Baltica, said the authorities could have acted with more consideration. “The Russian community feels offended,” he pointed out. “Many of them probably don’t even care about politics. This creates hatred on both sides, and I don’t think this helps Latvia’s unity.”

“Polarization has certainly increased, but I think it’s a short-term effect,” Katkins opined. “In the long term, it will decrease, which should be for the good of the Latvian people.”